In marked shift, the FDA is increasingly tolerant of single pivotal trials to support approval

Life Sciences

| By AMANDA CONTI

FDA traditionally required sponsors of new drugs to conduct two clinical trials to support approval. Now, in a new analysis by AgencyIQ, we find that FDA is increasingly relying on single pivotal studies to support the approval of new drugs, with the majority of all new drugs approved since 2020 leveraging just a single pivotal study to successfully clear regulatory review.

Background: The evolution of FDA’s standards for evidence

- When seeking approval from the FDA, companies must demonstrate “substantial evidence,” that their product is safe and effective when used as intended. The term Substantial evidence is defined under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics (FD&C) Act as: “Evidence consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations, including clinical investigations, by experts qualified by scientific training and experience to evaluate the effectiveness of the drug involved, on the basis of which it could fairly and responsibly be concluded by such experts that the drug will have the effect it purports or is represented to have under the conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the labeling or proposed labeling thereof.”

- Traditionally, FDA interpreted the need for well-controlled “investigations” to mean at least two clinical trials to support applications for new drugs or supplemental indications. However, this stance resulted in legal challenges against the agency. In one landmark case, Warner-Lambert Co. v. Heckler in 1986, several manufacturers sued the FDA after it ordered them to remove several indications from the labels of their oral proteolytic enzymes (OPE) products for lack of evidence.

- The Heckler case helped to refine the definition of “substantial evidence” in two important ways. First, the court determined that the determination of what constituted “substantial evidence” was within the purview of the FDA, to ensure a drug was “therapeutically significant rather than merely statistically significant.” Second, the court found that a single, well-done study could potentially suffice as substantial evidence in “exceptional” scenarios, though it did not determine that there was an overriding circumstance in the specific OPE case that would warrant a ruling against the two-study requirement.

- In 1997, Congress passed the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA), which—among other reforms— updated the definition of “substantial evidence” to allow for additional types of evidence, or “confirmatory evidence.” FDAMA d that the FDA can determine that data from one “adequate and well-controlled investigation” is sufficient to demonstrate safety and effectiveness if it is supported by “confirmatory evidence.” Following the FDAMA legislation, the FDA unveiled a foundational guidance document, Providing Clinical Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products in May 1998. The document focused on the quantity and quality of evidence needed to support efficacy claims, laying out examples and expectations for study designs.

Regulatory context: relevant guidance updates in recent years.

- Since the passage of FDAMA, the FDA’s acceptance of single pivotal trials has become more common, especially due to the increased submission of applications for products intended to treat, cure or prevent rare diseases or life-threatening conditions for which there is an unmet clinical need.

- As a result, FDA updated its 1998 guidance on providing clinical evidence of effectiveness in 2019, aiming to “complement and expand” on its scope. The new draft guidance document, Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products, offers the agency’s perspective on topics such as the appropriate use of external controls. It also permitted alternative trial designs and even suggested FDA might allow p-values “somewhat” higher than historically allowed. FDA has yet to issue a final version of the guidance.

- In September 2023, FDA released second, similarly-titled draft guidance specific to applications relying on a single clinical trial for which there is confirmatory evidence. The document, titled Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness Based on One Adequate and Well-Controlled Clinical Investigation and Confirmatory Evidence, spans 16 pages. As FDA makes clear, the single trial and confirmatory evidence are intended to be “considered together” to assess effectiveness.

- According to the draft guidance, the volume of confirmatory evidence needed is inversely proportional to the strength of the single adequate and well controlled study. In other words, there is no standard amount of confirmatory evidence needed to support a single study, and it instead depends on the features of the clinical investigation. While the guidance does not address safety studies, the agency does acknowledge that even if a sponsor could study efficacy in one study, a second clinical study is sometimes needed for approval to provide a full safety analysis that allows benefit-risk to be assessed.

- The bulk of the document lays out seven examples of data sources that could serve as confirmatory evidence and the situations in which they would be appropriate. FDA is clear that this does not intend to serve as an exhaustive list. [ Read AgencyIQ’s complete analysis of the guidance here.]

| Evidence Type | Use Case |

| Clinical evidence from a related indication | The indications, mechanisms of action, and efficacy endpoints have a high degree of similarity (e.g., using data from the therapy in a similar, already-approved indication) |

| Mechanistic or pharmacodynamic evidence | The disease pathophysiology and drug mechanism are both well-understood and straightforward (e.g., a drug’s mechanism of action corrects an enzymatic or genetic defect caused by a single gene and/or enzyme defect) |

| Evidence from a relevant animal model | The translatability of the pharmacological and pharmacodynamic data is robust, among other criteria (e.g., the assessment of an antimicrobial agent or a preventive vaccine in well-established infection models) |

| Evidence from other members of the same pharmacological class | A combination of factors is at play, including the sameness of the mechanism of action and measured effect, the similarity of endpoints measured, and number of drugs approved in the class. Generally, a greater number of approved drugs in the class increases confidence in the consistency of pharmacological effects. |

| Natural history evidence | There is uncertainty regarding the control group (e.g., a trial of a progressive disease in which the experimental group experienced stability and the control group experienced deterioration) |

| Real-world data (RWD) and real-world evidence (RWE) | RWD/RWE can serve as confirmatory evidence per the guidance, depending on the relevance, quality, and statistical analysis of the data, among other factors. Discussion with review divisions is important. |

| Evidence from expanded access use of an investigational drug | While “limited and inconsistent” information typically emerges from these programs, the information may be used if it is sufficiently detailed and reliable (e.g., a sponsor collects many case studies with detailed medical records and documented clinical results). |

AgencyIQ has sought to characterize the extent to which single pivotal trials have been leveraged for regulatory approval.

- A quick note about our methods: AgencyIQ reviewed drugs approved by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). CDER is the FDA office in charge of reviewing pharmaceuticals and therapeutic biologics. As such, it doesn’t review things like vaccines, blood products or gene therapies – those products are instead reviewed by CBER. All products are received in one of two forms: A New Drug Application (or NDA, for pharmaceuticals) or a Biologics License Application (BLA, for biologics).

- Novel drug products are defined as products that have never been approved for any indication. If a drug was previously approved for cancer, but is now approved for a cardiology condition, it would not be considered novel. The FDA also refers to novel products as “New Molecular Entities,” or NMEs. While the definition of NME has changed over the years, it can sometimes include a combination product consisting of at least one drug that has previously been approved. Data on these novel approvals is published throughout the year by both CDER and CBER. AgencyIQ compiles these data using information in approval letters, labeling and review packages posted to the Drugs@FDA database.

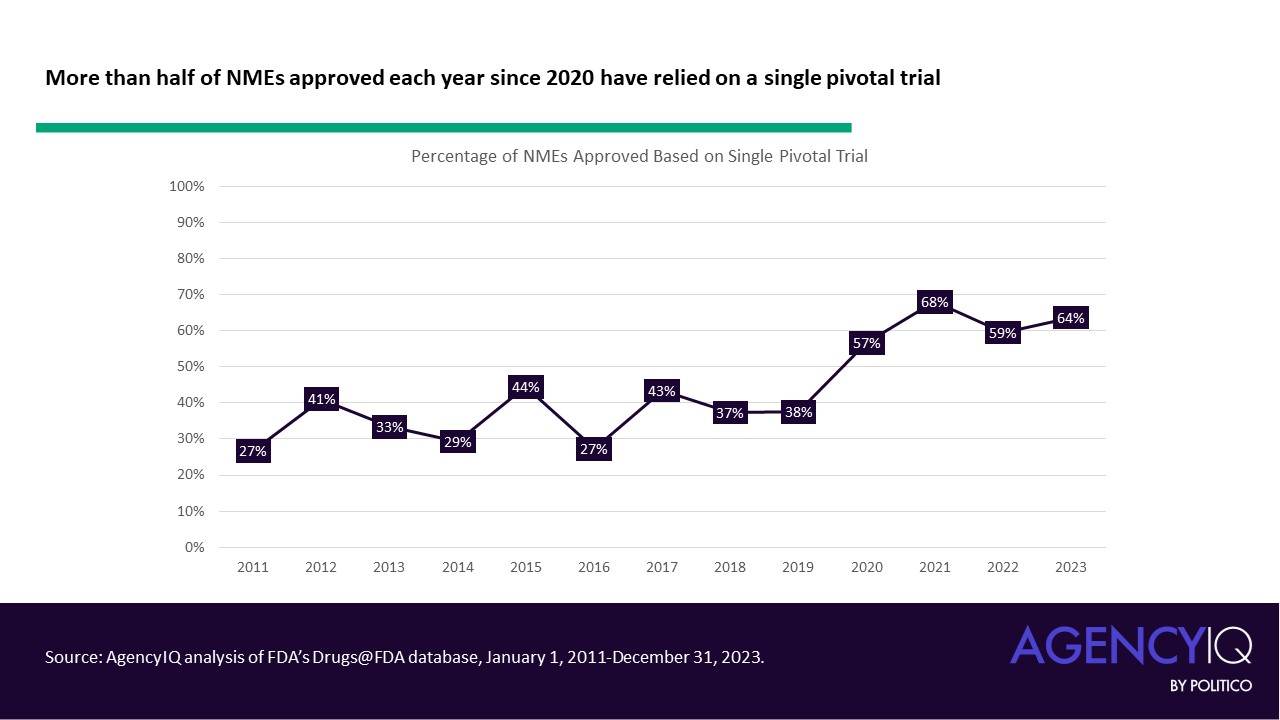

- AgencyIQ has previously analyzed the extent to which FDA has permitted new approvals based on a single clinical trial. In May 2020, AgencyIQ published an analysis showing that single pivotal studies are commonly and consistently used. For that analysis, AgencyIQ looked at all NMEs approved by CDER between January 1, 2011, and May 1, 2020. Some main takeaways: In this span, a quarter of all NMEs approved since 2011 relied upon a single pivotal trial, with the proportion ranging from 23% to 45% each year. According to AgencyIQ’s research, most of these drug products made use of priority review, and most products were for oncology indications.

Now we have an updated analysis on single pivotal studies, showing that this trend has accelerated dramatically in the post-pandemic era

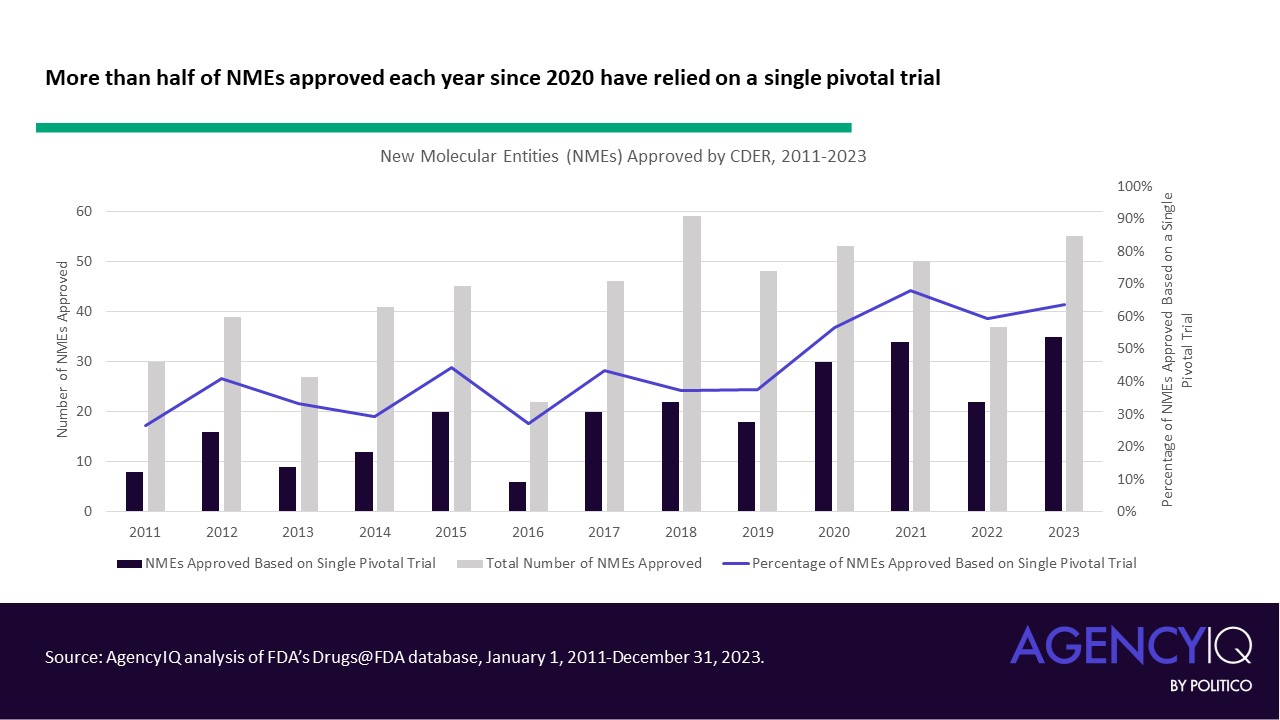

- The following analysis included NMEs approved by FDA between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2023. Despite the widespread disruptions to typical industry and agency activities wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic, the overall volume of NMEs approved by the agency remained relatively stable through these years. While the total number of novel drugs approved by CDER dipped to 37 in 2022, the agency recovered with 55 approvals in 2023, the second highest in a calendar year since 2011.

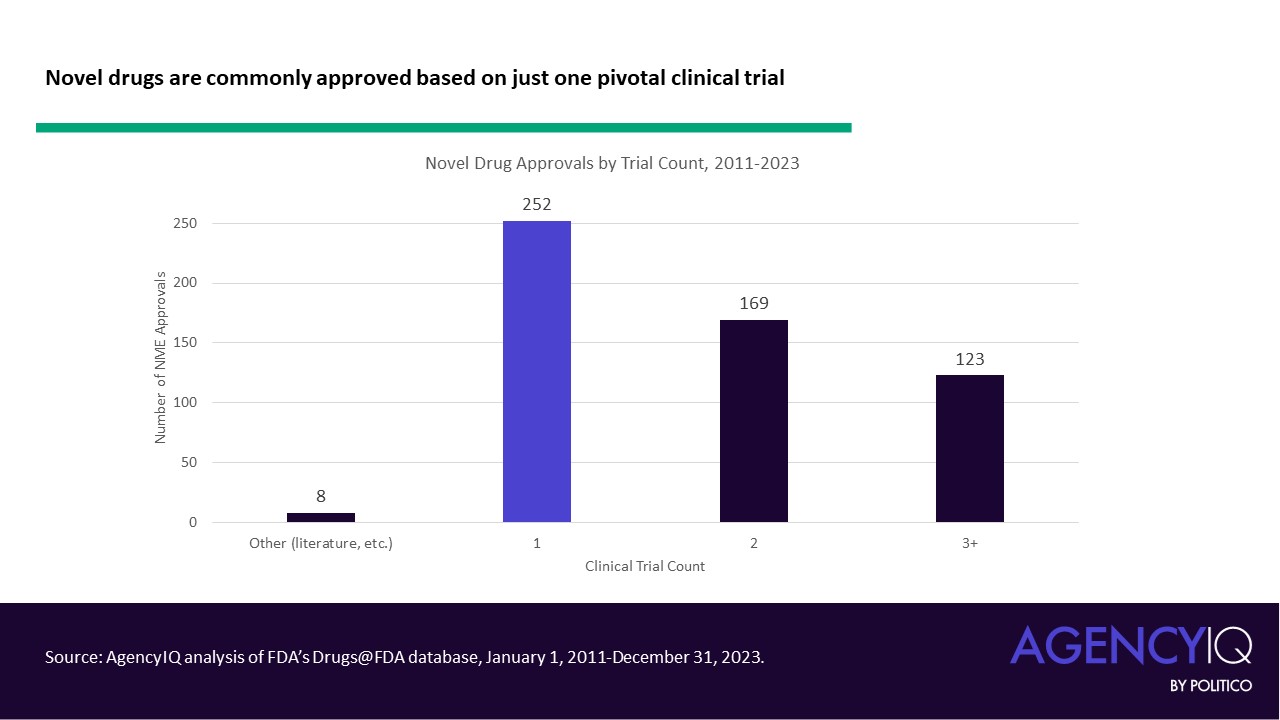

- Through 2023, it remains common for drugs to be approved using just a single pivotal trial. Altogether, more than 250 novel drugs were approved based on a single pivotal trial between 2011 and May 2020, according to AgencyIQ’s research. Since 2011, eight novel drug approvals were based on efficacy evidence other than pivotal clinical trials (such as in cases where an approval leveraged literature or FDA’s Animal Rule).

In recent years, the use of single pivotal trials to support novel drug approvals has boomed.

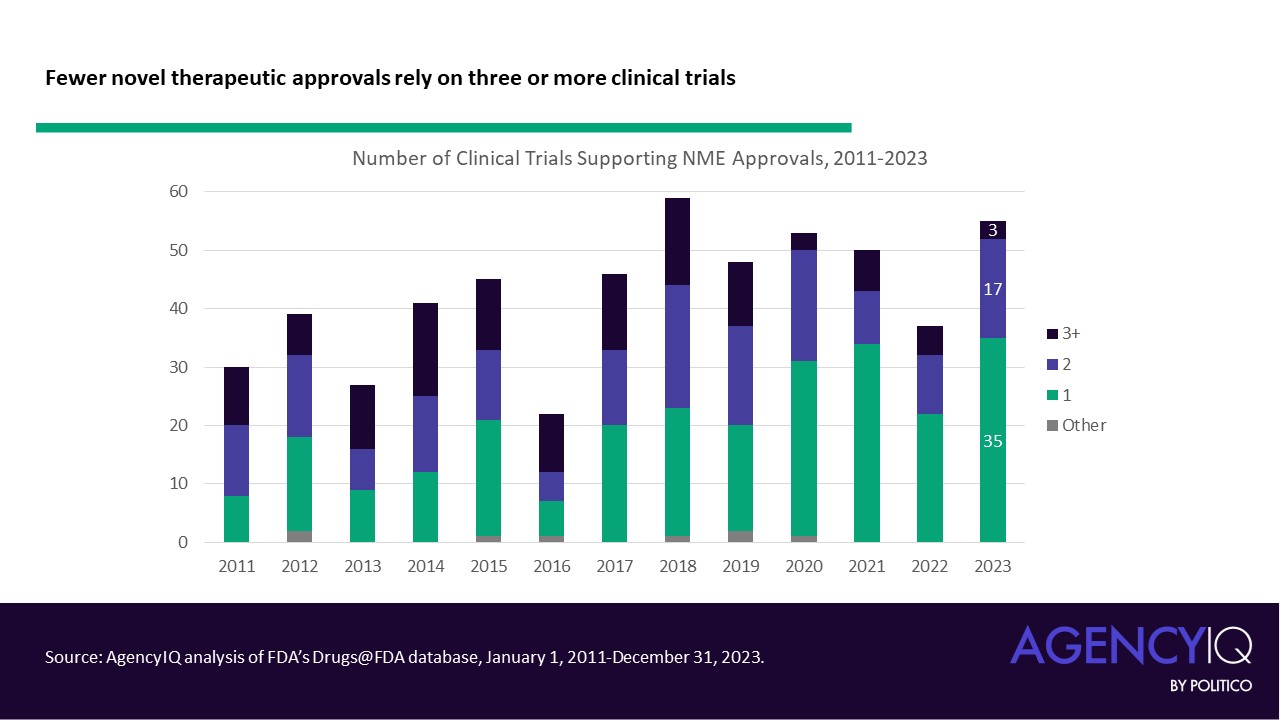

- Since 2020, the majority of NMEs approved each calendar year have relied on a single clinical. While the median number of pivotal trials was steady at 2 until 2020, the median has dropped to one trial since. Calendar year 2023 saw the highest number of NMEs approved based on a single pivotal trial, with 35 of 55 products listing just one clinical study in their original labeling.

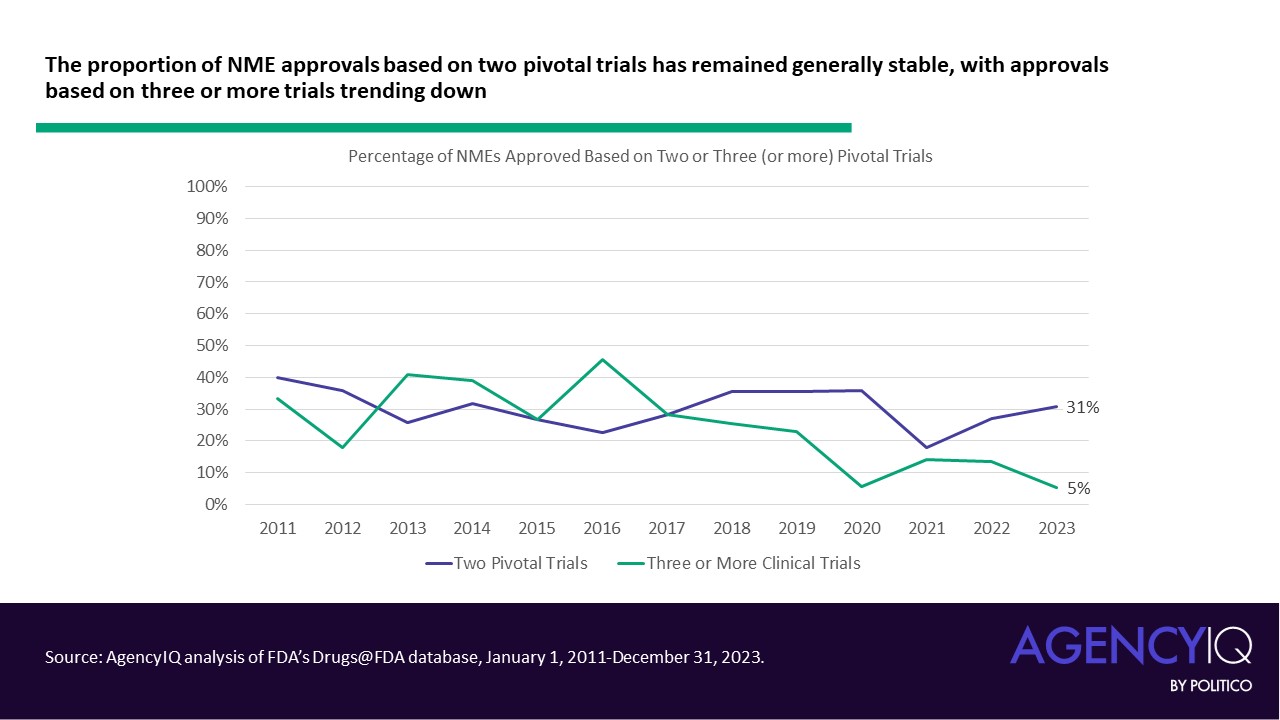

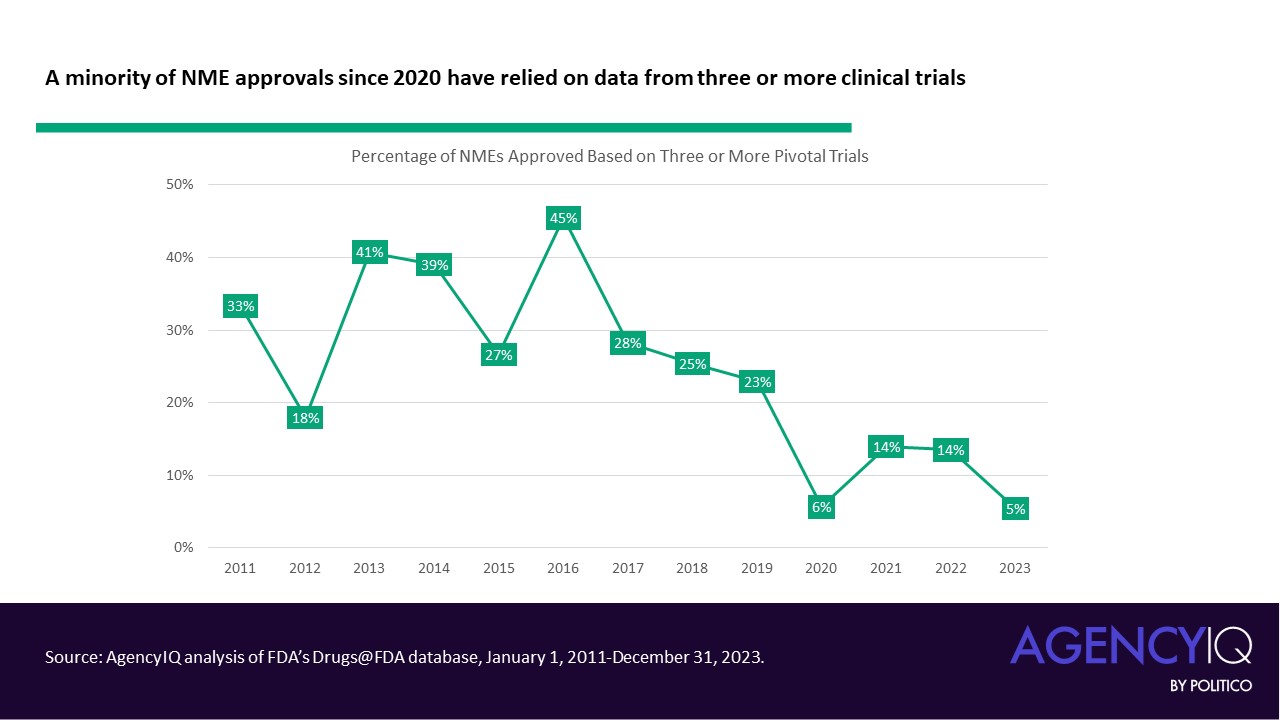

- In line with this trend, fewer NME applications are leveraging three or more clinical trials to support their approval in recent years. The volume and proportion of approvals based on two trials has remained consistent.

Understanding approvals based on single clinical trials

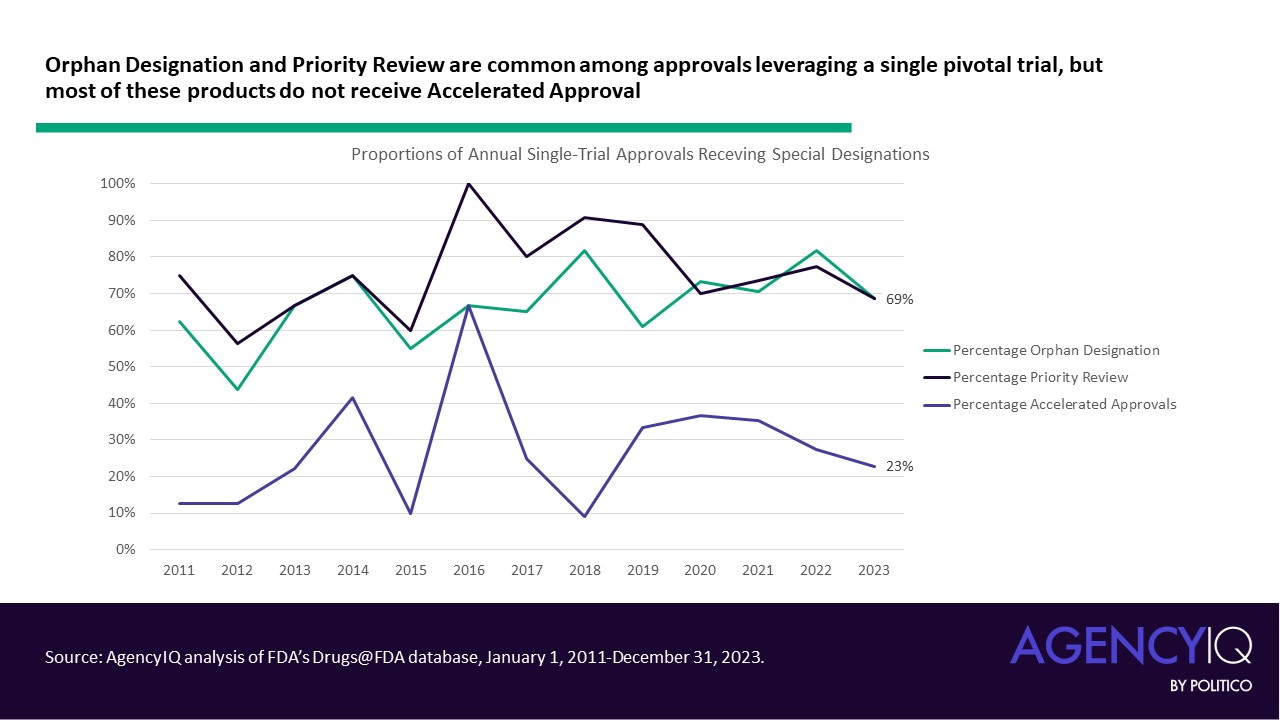

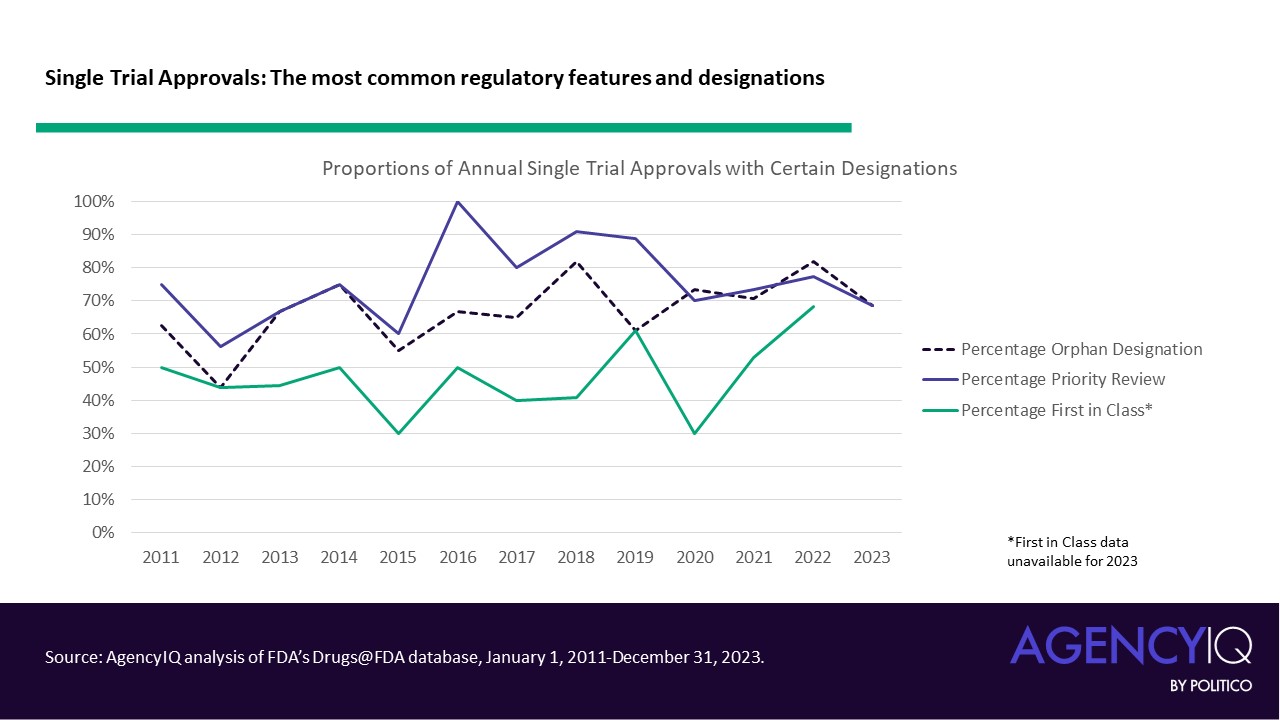

- Approvals relying on single pivotal trials often took advantage of FDA’s expedited review pathways for certain unmet needs. Most of these approvals received priority review, and many received orphan designation. As a refresher, products eligible for priority review must be for a serious condition and demonstrate the potential to offer a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness to patients with the condition. Orphan designation can be granted to drugs intended for prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of a rare disease (i.e., affecting < 200,000 individuals in the United States).

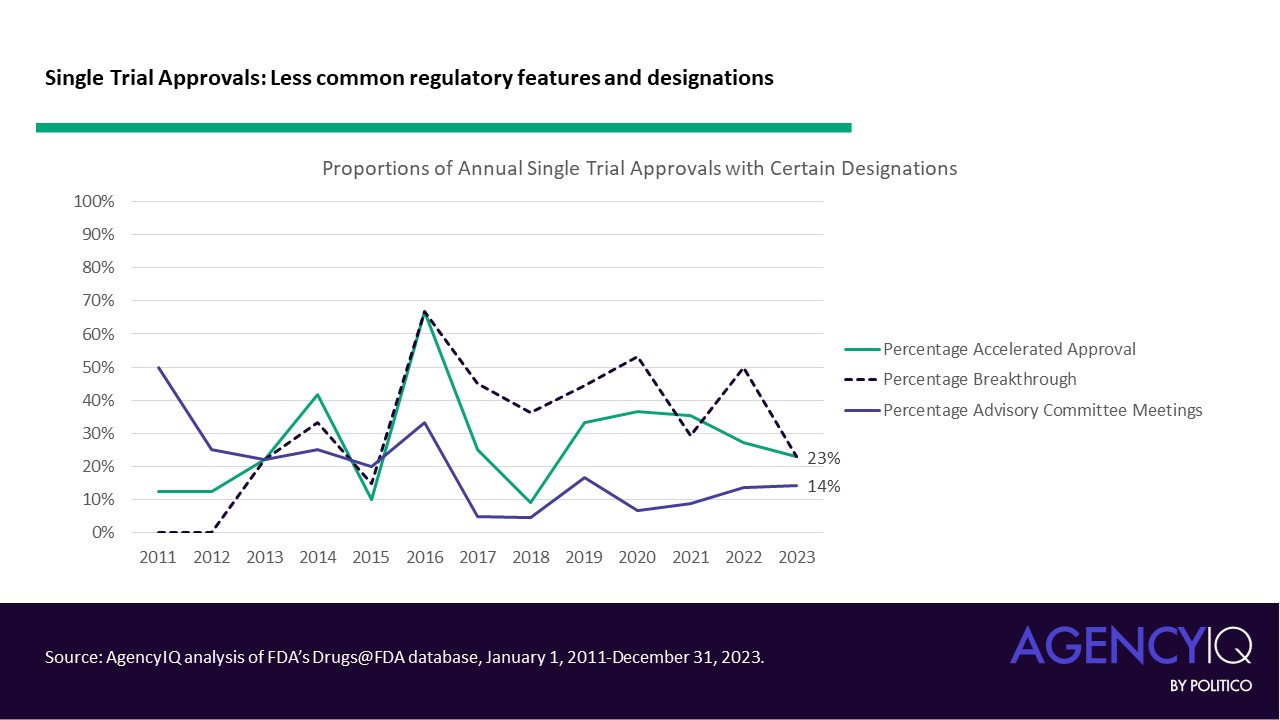

- On the other hand, certain features were less common in these approvals. FDA’s accelerated approval pathway was not a common mechanism for approval based on a single pivotal trial. Similarly, products approved based on one pivotal trial did not commonly hold Breakthrough Therapy designation, which FDA explains is granted based on “preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement on a clinically significant endpoint(s) over available therapies.” These approvals were also relatively unlikely to be considered by one of FDA’s Advisory Committees.

Moving beyond oncology indications

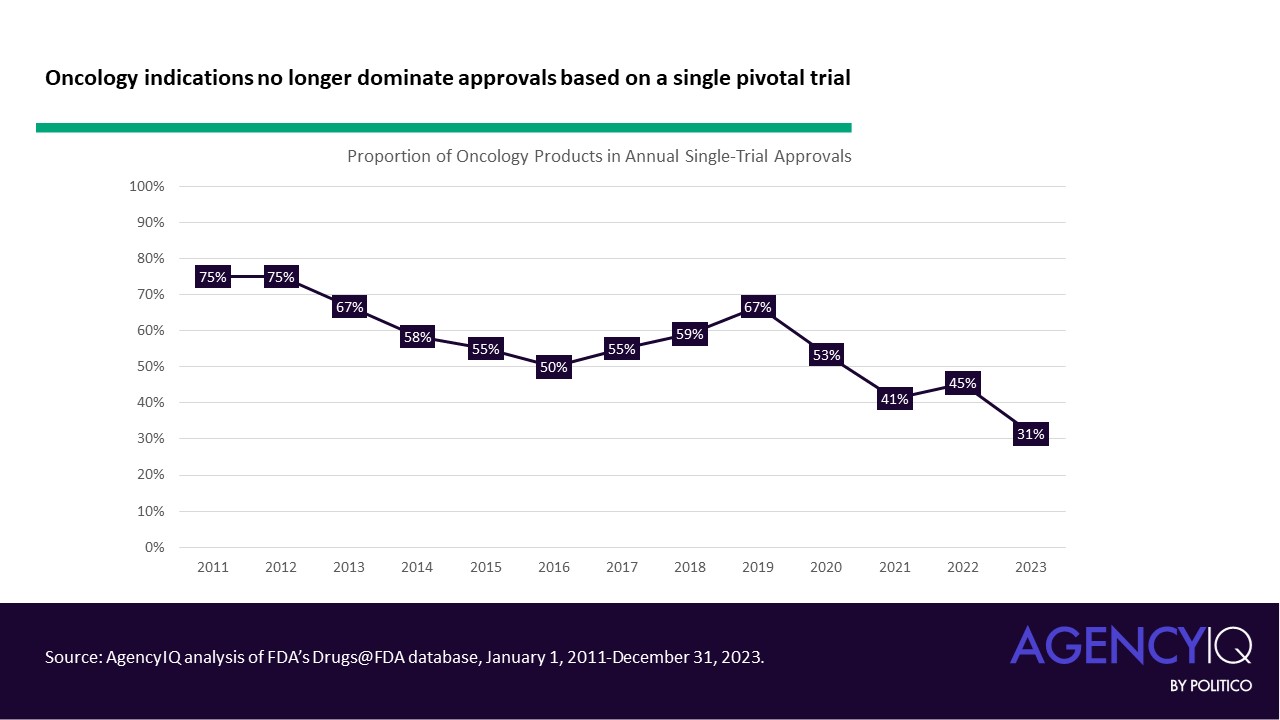

- Products with oncology indications formerly made up the bulk of approvals based on single trials, but the approach is increasingly being accepted by the agency in other disease areas. Oncology products consistently made up more than half of approvals based on a single clinical trial from 2011 to 2019, with a mean proportion of 62%. From 2020 through 2023, this mean proportion dipped to 43%.

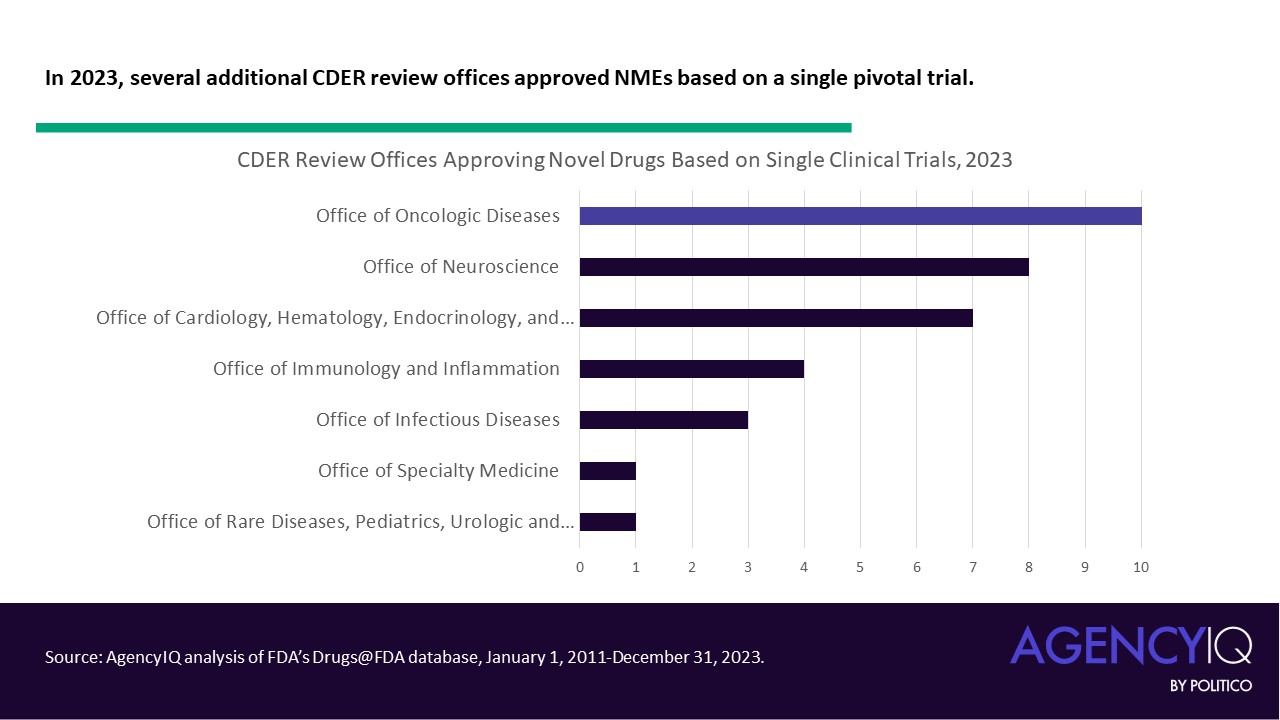

- What other indications have begun to see success with single pivotal trials? Looking more closely at one cross-section, just 31% of 2023 approvals based on a single clinical trial were under the purview of the Office for Oncologic Disease (OOD). The Office of Neuroscience (ON) and Office of Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology (OCHEN) trailed closely behind with 23% and 20% of these approvals, respectively.

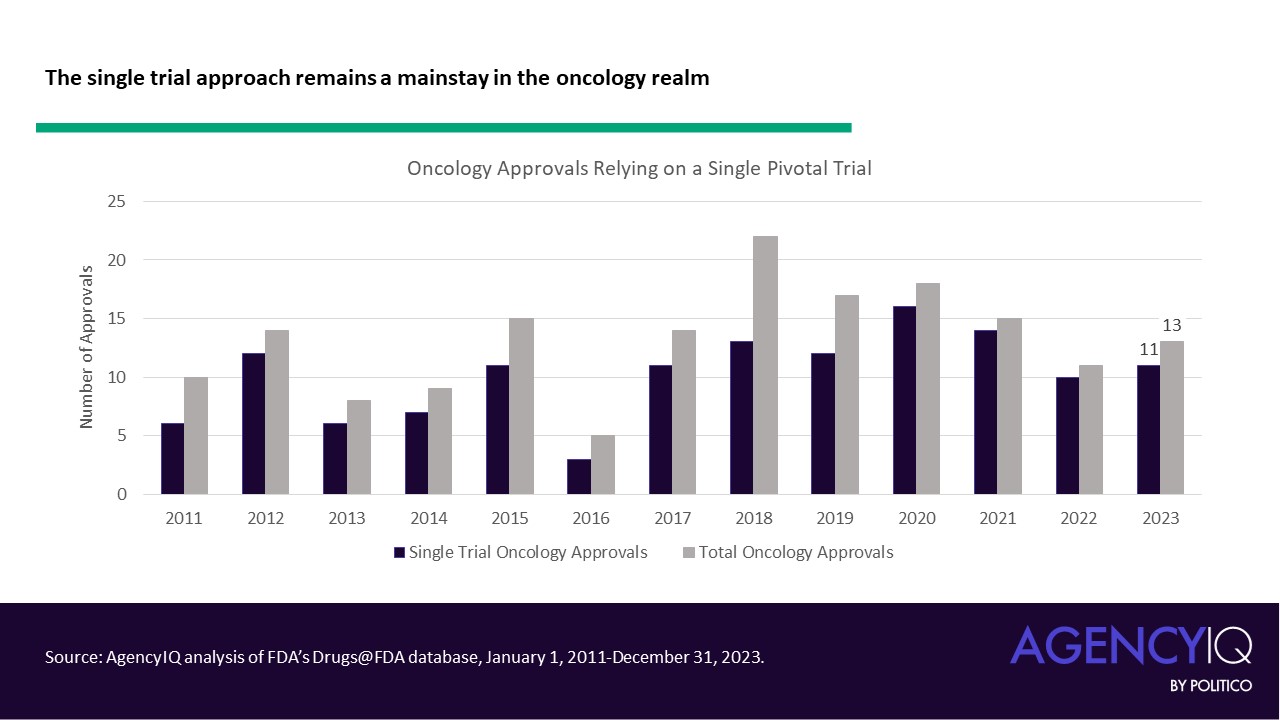

- Importantly, the single pivotal trial approach remains a mainstay of novel oncology product approvals. Since 2020, the overwhelming majority of oncology approvals have been based on a single trial.

How FDA handles single-trial approvals during review and after approval

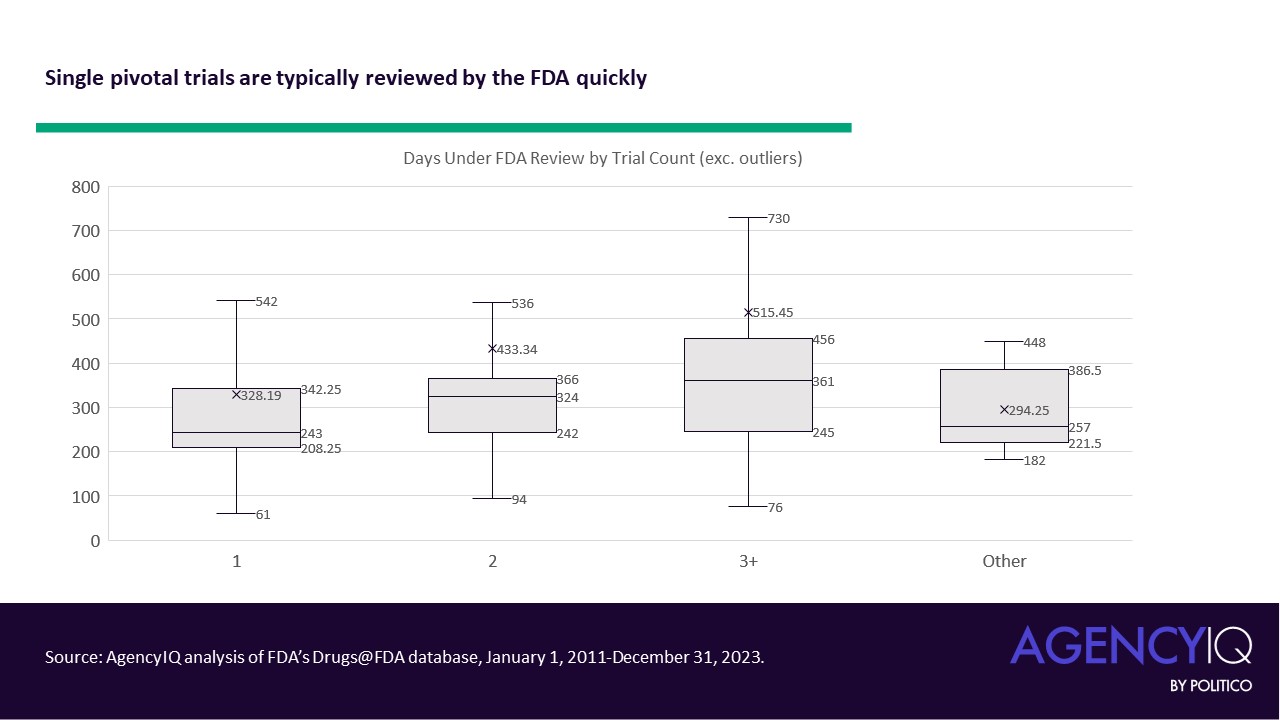

- A single pivotal trial does not appear to result in significant review delays by the FDA (e.g., if a reviewer found insufficient evidence to support a review decision). According to AgencyIQ’s analysis, of the 252 drugs approved using a single pivotal study, 82% were approved during the first review cycle and 97% met their target date under the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA). Most were also approved in the first calendar year of review (measured in actual days, and not FDA review days), with an average of about 328 days. In general, the data suggest that more clinical trials are associated with greater durations of review (note: outliers, like gepirone’s 24-year review, were excluded from the analysis below).

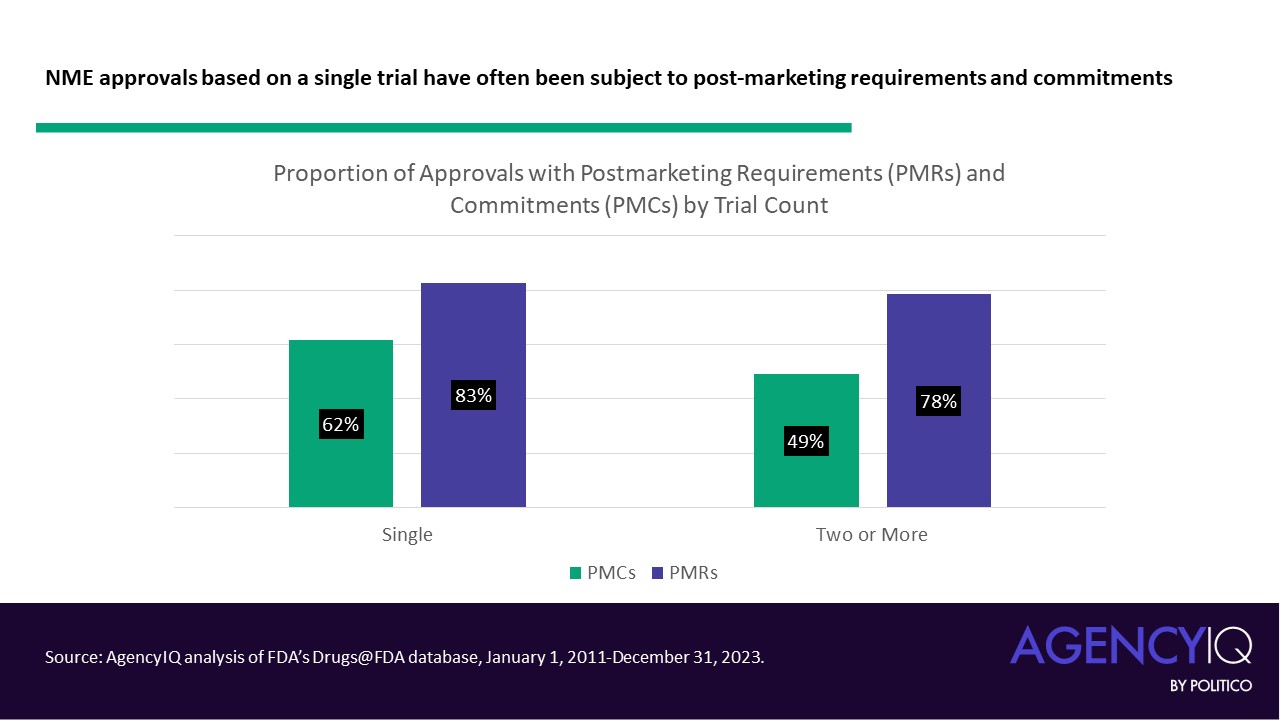

- While some may reasonably predict that studies with one trial may be subject to longer post-marketing to-do lists, our analysis signals that this is not necessarily the case. A slightly larger percentage of approvals based on single clinical trials have post-marketing commitments (PMCs) and post-marketing requirements (PMRs) and when compared to approvals based on two or more trials. That said, the difference is less pronounced for PMRs.

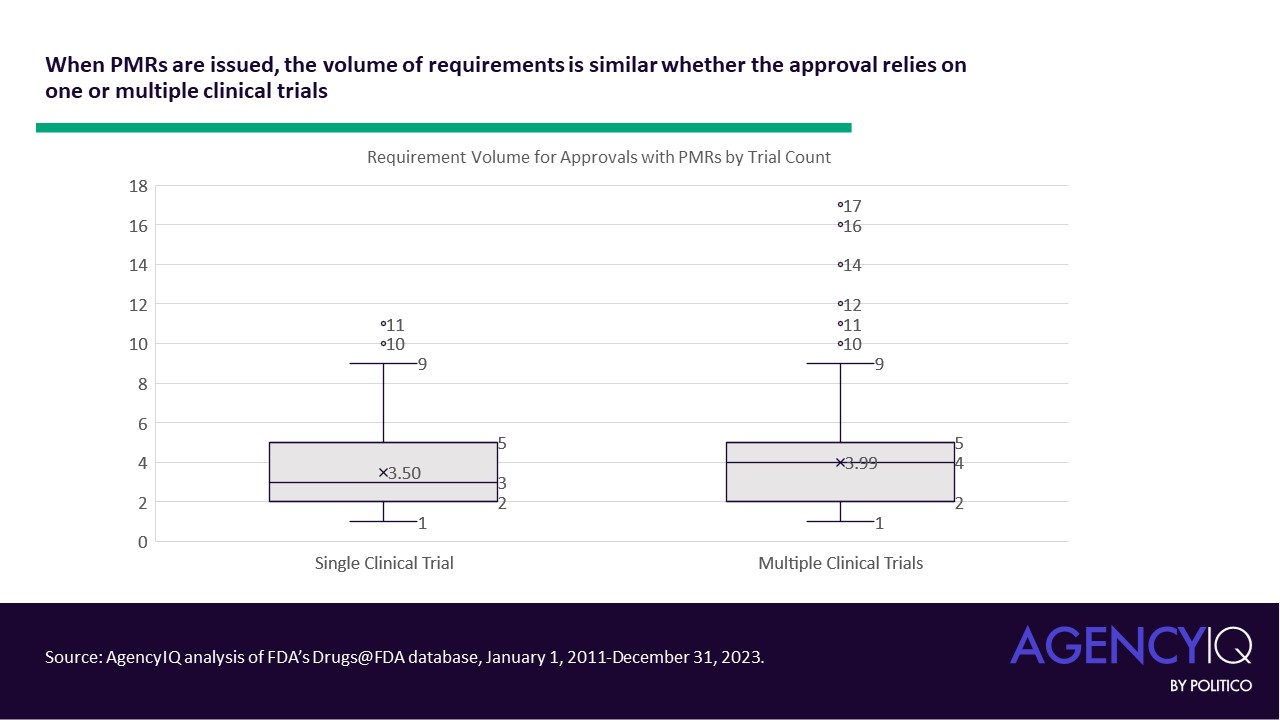

- In general, FDA does not seem to issue a higher volume of PMRs in approvals based on a single pivotal trial. This volume was calculated as the sum of individually enumerated Pediatric Study requirements, Accelerated Approval verifications, and/or 505(o)(3) safety study requirements in a product’s original approval letter.

Analysis

- This analysis was limited in scope, only assessing the clinical trials supporting novel product approvals. That said, other research has indicated that supplemental applications for additional indications are even less likely to be supported by evidence from two pivotal studies than the original indication. An analysis by Yale and Duke researchers published in JAMA Network Open in 2021 showed that just 15.8% of supplemental new drug applications (sNDAs) and supplemental biologics license applications (sBLAs) approved by the FDA between 2017 and 2019 were based on at least two pivotal trials [ Read full AgencyIQ analysis here.].

- FDA’s apparently increasing openness to single pivotal trials to support the approval of novel drugs represents a huge change in the clinical trial enterprise. While the data indicates that the agency continues to reserve this posture for serious conditions with unmet need (i.e., orphan designations and priority review), recent approvals show that the approach is being leveraged for a more diverse array of indications, especially in the field of neurology. This approach, if considered more widely, could lower the costs of drug development by allowing companies to obtain approval using fewer clinical studies, which are generally costly to companies.

- But for payers and providers, there is a risk to this approach. The decision to rely on multiple clinical studies isn’t just bureaucratic – it’s meant to significantly increase the likelihood that evidence obtained in a clinical study is accurate and can be relied upon. With only one study, the chance that a trials’ finding – the same used to support approval – is inaccurate or unreliable increases. While confirmatory evidence in the form of additional information or confirmatory evidence can help reduce these chances somewhat, they may not be sufficient to satisfy the evidentiary requirements of some insurers or the clinical use requirements of some clinicians.

Featuring previous research by Kedest Tadesse.

To contact the author of this item, please email Amanda Conti ( aconti@agencyiq.com).

To contact the editor of this item, please email Alexander Gaffney ( agaffney@agencyiq.com)